|

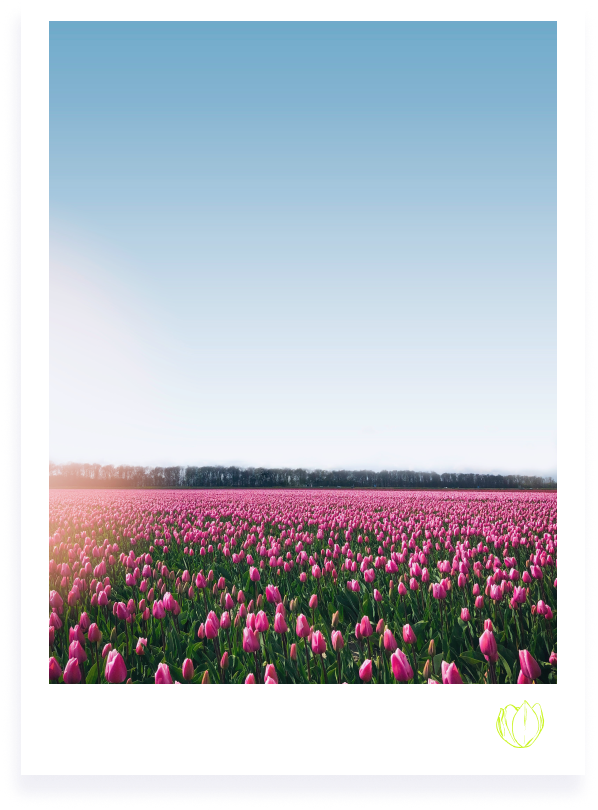

The TULiP Lab's name was inspired by a quote from Dr. Marsha Linehan, the psychologist who developed Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) for the treatment of people who have Borderline Personality Disorder.

If you are a tulip, don't try to be a rose. Find a tulip garden. Find the environment that you will fit into, that will appreciate you.

— Dr. Marsha Linehan

Developer of Dialectical Behavior Therapy The idea behind this metaphor is that part of recovery involves accepting oneself for who one is, even if other parts involve changing. The people to whom our work is devoted often come from painful and invalidating environments that have led them to believe that they are broken for feeling emotions in ways that are different from others. We disagree. At the TULiP Lab, we believe that no one is fundamentally broken and that everyone can find freedom from suffering and a life worth living.

Our work is intended to help move people towards their vision of such a life, even if they cannot yet see it for themselves. |

The TULiP Lab (Treating and Understanding Life-Threatening Behaviour and Posttraumatic Stress) is a research group dedicated to helping people build lives worth living. We optimize interventions and identify treatment targets for individuals who engage in life-threatening behaviour, have borderline personality disorder (BPD), and/or have posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

We approach these goals in two ways: First, we ask clinically-relevant questions about BPD and its treatment—Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT)—using experimental, ecological momentary assessment, and longitudinal methods. In this line of research, we seek to understand BPD and life-threatening behaviour, identify key treatment targets, and examine the efficacy of specific treatment strategies for BPD and life-threatening behaviour.

Second, we draw on clinical trial methods to optimize and simplify the treatment of BPD and PTSD. To this end, we have recently become particularly focused on harnessing the power of relationships to treat BPD and/or PTSD through conjoint and dyadic interventions, as well as identifying simple, streamlined, and efficient ways of treating BPD, life-threatening behaviour, and PTSD.

We approach these goals in two ways: First, we ask clinically-relevant questions about BPD and its treatment—Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT)—using experimental, ecological momentary assessment, and longitudinal methods. In this line of research, we seek to understand BPD and life-threatening behaviour, identify key treatment targets, and examine the efficacy of specific treatment strategies for BPD and life-threatening behaviour.

Second, we draw on clinical trial methods to optimize and simplify the treatment of BPD and PTSD. To this end, we have recently become particularly focused on harnessing the power of relationships to treat BPD and/or PTSD through conjoint and dyadic interventions, as well as identifying simple, streamlined, and efficient ways of treating BPD, life-threatening behaviour, and PTSD.

MORE INFORMATION

FAQS

|

WHAT IS BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER (BPD)?

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a mental illness that affects approximately 1-6% of the general population. BPD involves dysregulation in emotions (e.g., large, frequent, and painful), identity (e.g., not having a clear sense of oneself), behaviour (e.g., self-harm, suicidal behaviour, impulsive behaviour such as substance use), relationships (e.g., frequent conflict in relationships, fears of abandonment), and cognition (e.g., dissociating, or disconnecting, from reality; American Psychological Association, 2013). Leading theories of BPD suggests that emotion dysregulation (i.e., difficulties with intense emotion and changing that emotion) is the core of BPD (e.g., Linehan, 1993). These theories suggest that BPD symptoms are either direct consequences (e.g., anger outbursts) or destructive attempts to manage (e.g., self-harm) emotion dysregulation (Linehan, 1993). BPD can be a life-threatening condition, as 84% of individuals with BPD have engaged in self-harming behaviour at some point in their lifetime (e.g., Grant et al., 2008) and 10% die by suicide (Paris & Zweig-Frank, 2001). However, BPD is also highly treatable (see description of dialectical behaviour therapy, above). The TULiP lab seeks to identify ways to de-stigmatize and refine treatments for BPD, so that more people with BPD can find effective and efficient help. WHAT IS DIALECTICAL BEHAVIOUR THERAPY (DBT)?

Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993) is an evidence-based cognitive-behavioural therapy that was developed by Dr. Marsha Linehan in the late 1980s. DBT is the gold-standard evidence-based intervention for borderline personality disorder and chronic suicidal behaviour (De Cou, 2019). Standard DBT includes four primary modes: individual therapy, group skills training, 24/7 phone access to DBT clinicians, and DBT clinicians attending a consultation team to support each other and help them remain effective in administering DBT. Three primary philosophies underpin DBT: Zen Buddhism, behavioural science, and dialectical philosophy. These philosophies translate to a therapy that involves a simultaneous (i.e., dialectical) focus on both acceptance (i.e., derived from Zen Buddhism) and change (i.e., derived from behavioural science). This dialectical integration of both acceptance and change is believed to be essential in helping clients in DBT build a life worth living (Linehan, 1993). The TULiP lab is actively interested in identifying ways to disseminate DBT to more people, refine its efficacy, and identifying its essential and active ingredients. WHAT IS POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER (PTSD)?

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a mental illness that affects approximately 6.1-9.2% of individuals in Canada and the United States (Van Ameringen, Mancini, Patterson, & Boyle, 2008; Goldstein et al., 2016). PTSD may develop following exposure to a traumatic experience (e.g., actual or threatened death, serious injury), and is characterized by a combination of symptoms from four distinct “clusters” which persist longer than one month (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The first cluster is re-experiencing, where the individual relives the traumatic experience (e.g., recurrent nightmares, flashbacks). The second cluster of symptoms is avoidance, which could be of situations associated with the trauma, as well as of other trauma-related emotions, thoughts or memories. The third cluster is negative changes in mood or cognition, which may include persistent and exaggerated negative beliefs (e.g., blaming oneself for causing the trauma), the loss of interest in activities, or being unable to feel positive emotions (e.g., happiness, love). The fourth symptom cluster is alterations in arousal and reactivity, which may involve irritability, self-destructive behaviour, or being easily startled. The TULiP lab aims to further understand trauma-related pathology, and aims to optimize PTSD treatments independently and in their treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. |